27 February 2014

Could the physical classroom become redundant as teaching centres beef-up their wireless communications networks? PHOTO: CISCO

Just as IT managers in the 1980s found it impossible to resist PCs creeping into the workplace, schools and colleges now face a plethora of mobile devices in the classroom. How are they coping with ‘Bring Your Own Device’? IAN GRANT finds out.

Here’s the upside to BYOD in the classroom: you get rid of textbooks (as all course material is delivered from centralised cloud servers); manky school satchels and rucksacks disappear, (improving student posture); PCs vanish from school budgets (and reappear on the parents’); teachers hardly need classrooms because students can get everything online (and they can give personalised attention to those that need it).

But what’s the reality? Too little bandwidth; few standards; coursework that’s not digitised; coursework that you can see properly only on one device; teachers that are neither technically nor pedagogically trained to take advantage of the technology; identity management and authentication issues; network and data security issues; and too little money.

“Schools and parents have jumped (into BYOD) with both feet without really looking,” says James Griffiths, senior pre-sales engineering with Boston Networks which has installed wireless networks in hundreds of Scottish classrooms. He reckons the situation is particularly bad in private schools. Parents have bought tablets (typically iPads) for their kids and now insist the schools increase the return on that investment beyond expertise at Candy Crush and downloading stuff from BitTorrent sites. Public sector schools seem to be better organised in terms of equipment procurement, but both remain stymied by the impact of BYOD on network bandwidth, management and content provision, according to Griffiths.

Part of the problem is organisational. The distributed structure of education in the UK makes it hard to develop standards and create economies of scale in procurements. It is difficult to discover how much money is actually spent on computers, access devices and networks in education.

That said, figures from the Institute for Fiscal Studies and the UK Public Spending website reveal that more than £88bn will be spent on education this year. That’s 12 per cent of the national budget or about 4.6 per cent of national income. The ones actually doing the spending include the country’s 163 universities and colleges, and 32,746 primary and secondary schools. The potential market of learners is close to 10.6 million, of which 8.25 million are in schools and 2.35 million are in higher education.

Despite 32 years elapsing since the BBC Micro was launched, there appear to be only patchy examples of good practice in applying digital devices to educate and train citizens. This is also despite a 2003 report from the Joint Information Systems committee (the forerunner to education technology consultancy, Jisc) which warned that mobile digital devices were likely to completely change the classroom and teaching.

It said: “The concept of teaching per se is moving away from the ‘whole course’ approach towards the provision of resources which can be combined to give the students the individualised learning experience they increasingly want. E-textbooks and e-learning content must also be seen in a (higher education) context now rich in digital content of all kinds, much of which is purchased, licensed and mediated through the library.” Today, for “library” you can substitute “cloud”.

Early adopters

Educational establishments were among the first to wake up to the advantages of wireless networking, not just for administration, but also in the classroom. After all, Cat5 and Cat6 cabling is expensive and inflexible once installed. As a result, wireless vendors such as Cisco, Meraki, Meru, Ruckus Wireless, Xirrus, et al have done very well. Now it’s time for Wireless Classrooms 2.0.

Those initial networks paved the way for schools and colleges to consider moving to a BYOD policy for both staff and students. This is seen as a way to relieve budget pressures, expand ‘computer literacy’, replace textbooks, supplement course content, speed up admin, and generally prepare students for life outside the cloister. But all this raises a lot of other issues.

Jisc management operations expert Jason Curtis says mobile devices in classrooms are like rabbits: “They’re cute and they are multiplying at an enormous rate. People have underestimated what’s going on.”

Noel Davis, a technology expert with Jisc, adds that keeping up with the rate of change in the technology has been a big problem. Previous efforts have variously brought in PCs, PDAs, laptops, netbooks and mobile phones. But tablet-based computing has the potential to revolutionise how students are taught – indeed, how they learn. He notes it is not yet four years since Apple introduced the iPad and really brought mobility to the education market. Already, we are on the fifth generation of tablets with others such as Microsoft’s Surface just starting to gain traction.

BYOD hits the schools

Renfrewshire Council has hired local network integrator Boston Networks to design and install the infrastructure for a council-wide wireless LAN rollout at 63 schools. This follows a similar Boston project for hundreds of schools in Dumfries and Galloway.

The network will extend the council’s existing LAN across its schools estate to enhance the virtual working environment and provide mobility. Users will start with council-provided devices to access resources, but the infrastructure will also enable BYOD and public access, if needed.

Boston designed the communication infrastructure and structured cabling networks to connect more than 550 wireless access points throughout every school campus within the Renfrewshire estate. In addition to deploying Brand- Rex Cat6 structured cabling, Boston also upgraded and installed more than 150 network cabinets to accommodate PoE and enhance the wireless LAN.

Elsewhere, London’s Giffard Park Primary School faced an influx of Wi-Fi-enabled devices that now consists of 219 notebooks, 20 laptops, and 14 tablets. It is also planning to migrate pupils from netbooks to iPads over the coming year, so needed to future-proof its wireless network.

Natalie Goodman, the school’s business manager, said the existing wireless network had been in place for about five years but didn’t provide complete coverage. “We regularly experienced coverage blackspots and it wasn’t fast enough to deliver learning in a seamless way.”

As a result, Giffard Park now has a network based on Xirrus’ arrays which support two to 16 radios. This will enable it to upgrade and scale in line with changing user demands. The wireless network will facilitate the delivery of digital learning within every subject, with mobile devices provided for all Key Stage 2 pupils.

While Pythagoras’ Theorem hasn’t changed in 2,500 years, the rate at which hardware becomes obsolete/uncool tracks Moore’s Law. Matching content to the delivery medium to transfer the knowledge more effectively is still an art. Davis says the plethora of screens and operating systems means content developers should now be working in HTML5 just to get around the issues associated with displaying their content properly.

He also notes that most learning establishments are unprepared for the hit on their networks in terms of bandwidth, access management and security. Half a dozen students latching onto a traditional 2.4GHz Wi-Fi hotspot are enough to kill it. 5GHz APs should therefore now be the minimum, according to Davis. Boston’s Griffiths adds that schools are now starting to specify the 802.11ac standard, ratified only in January 2014, which will provide 1Gbps links in the classroom.

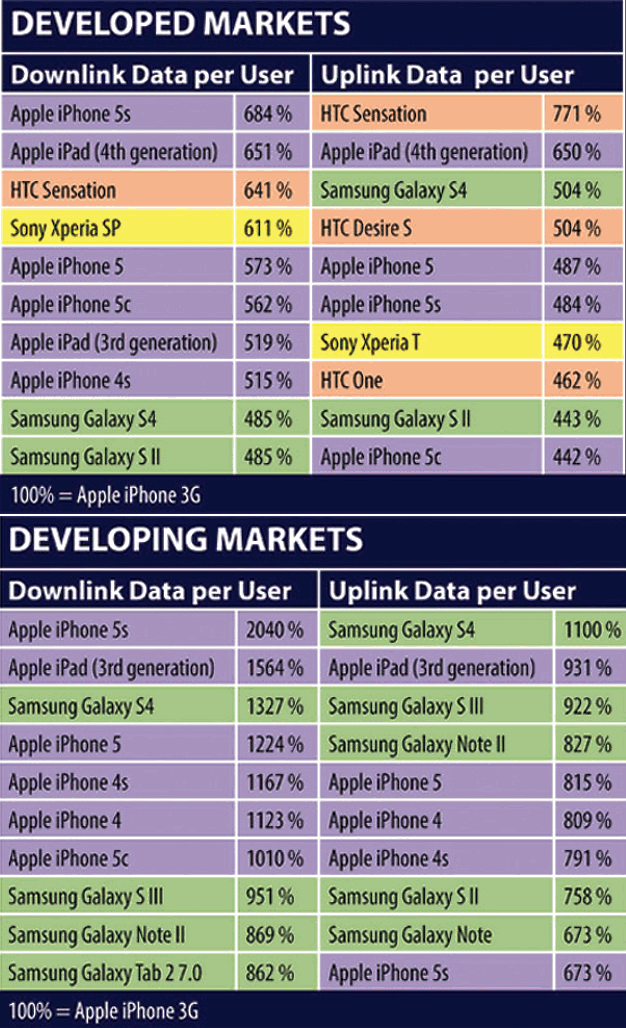

That’s not all. A recent study by JDSU (which is best known for its test and measurement gear but is now also a networking location expert since its acquisition of Arieso) showed that users of Apple devices are the most greedy “data hogs” (see table left). The survey found that iPhone 5 users download seven times as much data as its benchmark iPhone 3G users do. And iPad 4 users are close behind at 6.5 times. Samsung users uploaded more stuff. Other researchers have found most classroom traffic is download, which suggests interactivity or at least peer-topeer learning is still latent.

Few education authorities factored any of this into their calculations when they specified their earlier Wi-Fi networks. And the indications are that few do today. But the impact on bandwidth is huge. Speaking about the wider market, JDSU CTO Michael Flanagan says the fact that 0.1 per cent of 4G subscribers consume half of the data may prompt operators to identify these extreme users. “This in turn may make it easier to deploy small cell and Wi-Fi access points to ease network congestion. However, the accuracy of these placements should be of paramount importance to operators due to the limited range of the small cells and Wi-Fi.”

Backhaul

Since classrooms will generate a lot more (bursty) traffic than average hotspots, schools and colleges may offer to backhaul 4G traffic over their Wi-Fi and fibre connections. However, there are regulatory barriers to the use of public assets for private purposes and profit. Nonetheless, backhaul remains an issue alongside bandwidth. Brian Durrant, CEO of the London Grid for Learning Trust (LGfL), took early steps to ensure that the 2,500 schools he serves are adequately provisioned. “The rollout of LGfL 2.0 was completed at the end of 2012 and 2,500 London schools are benefiting from a fast, reliable service at lower overall costs. Schools are served with an uncontended, symmetrical service at bandwidths from 10Mbps to 1Gb, depending on their size and budgets; 10Gbps would be available if required and financed.”

The London Grid is said to be the largest educational metropolitan network in the world. It was deployed by Virgin Media Business (VMB) and runs Ethernet over fibre using Juniper’s Junos network operating system to connect primary and secondary schools in the Greater London area. When the VMB deal was signed in June 2010, the Grid expected to save £131m per year.

Brian Durrant, CEO, London Grid for Learning

“BYOD can be very attractive from a curriculum perspective, allowing pupils to have a greater degree of ownership of their own learning. It extends learning activity beyond lesson time and the school gate.”

According to Durrant, schools need to exercise caution in opening their local networks to devices brought in by pupils and staff. “BYOD can be very attractive from a curriculum perspective, allowing pupils to have a greater degree of ownership of their own learning. It extends learning activity beyond lesson time and the school gate.

“On the downside, allowing such devices onto the school network has security and safeguarding implications. Schools which consider miscreant behaviour a possibility will usually (for example) disable USB ports on school-owned devices to prevent inappropriate content or tools (proxy anonymiser technologies, for instance) being used. Obviously, allowing users’ own devices to connect to the school LAN effectively re-opens the way.”

Durrant recommends that any school that considers allowing, for example Wi-Fi access, should first consider creating a separate and secure VLAN. That way, BYOD and authorised traffic is kept separate.

While congestion in the classroom wireless network is likely to remain an issue for the time being, more bandwidth may arrive in the form of access via the LTE mobile networks now being built. O2’s licence requires it to provide indoor coverage to 98 per cent of the UK, and EE and Vodafone are likely to follow suit. This means students could use the mobile network either as a primary or alternative way to access the local Wi-Fi system. There are already anecdotal reports of students using their own data plans rather than the classroom network to go online.

While Jisc’s Davis believes LTE will be a “big help”, Durrant is more nuanced: “LTE, where available, is a service to the device from an external provider in the same manner as 3G or HSPA. This service would usually be unfiltered, unmonitored and outside of any control exercised by the school. BYOD, for which the user has an external (usually unfiltered) internet accessing account, is a matter for local school policy, much as permitting or proscribing mobile phones in the classroom. Hence, LTE in this context is unlikely to supersede Wi-Fi, with which (given appropriate configuration) a school can at least exercise a degree of access control.”

Jason Curtis, management operations expert, Jisc

“HTML5 still has some problems but it’s the best solution there is at the moment. They really need to get their skills up, and there needs to be better tools to produce content more easily for crossplatform delivery”

LAN lockdown

Locking down the LAN may be counterproductive. So too is restricting the choice of device. Several sources says that while centralised purchasing can help to lower cost per device, learners are more likely to become expert users of the device of their choice, and therefore more likely to use it to access content in the classroom.

Ennio Carboni, president and GM for network and IT operations management at Ipswitch, says “COPE” (companyowned products and equipment) policy control probably won’t work in the long term. Instead, he believes a hybrid solution that gives users the choices they want but protects the corporate assets (data and content) is needed.

Carboni points out that the big US universities have been extremely proactive in this field. “Every September, thousands of new (and increasingly digital native) students arrive with their mobile devices, and the first thing they want is to get connected. As a result, universities have become adept at provisioning user accounts, setting up authentication processes and using network policy management tools to control bandwidth, access to content, and other permissions.

BYOD – not the death of the textbook

Textbook publishers the world over need to change their business model in the face of BYOD to the classroom.

According to the Publishers’Association, the sale of school textbooks rose four per cent in 2012 to £290m, thanks largely to a 51 per cent rise in the sale of digital products to £13m. The proportion of digital to paper sales has stayed constant at around four per cent for several years. But is this due to publishers’ reluctance to create digital content, schools’ capacity to absorb and apply it, or something else, like copyright and digital rights management?

The answer is not clear. But the industry experts we spoke to were unanimous that future course material needs to be produced using HTML5. This will avoid the problems associated with publishing content to devices with different operating systems, browsers and screen formats

The pan-European 2010Motill study into mobile learning (mLearning) found that it offered an excellent way of socialising education, helping small groups to integrate with society. It also broadens the learning field as students invariably read wider and deeper into their subjects.

However, it concluded national accreditation of e-learning courses remain problematic, curricula need to be re-organised to accommodate mobile learning, and that open content systems are viable but need more work. Motill also noted that new ways to finance mLearning are required because educational institutions have found it hard to integrate it into existing admin and educational processes.

Jisc’s Curtis agrees, and says that most people will behave themselves online provided the policies are sensible and fair and the reasons properly explained. Davis adds that educators need to stop focusing on the end point device: “Service delivery is the thing they need to think about. Whether it’s Google Docs, Microsoft Office 365 or virtual desktop infrastructure, they have to focus on service delivery and content types. HTML5 still has some problems but it’s the best solution there is at the moment. They really need to get their skills up, and there needs to be better tools to produce content more easily for cross-platform delivery.”

-(002).png?lu=245)