28 October 2014

Desktop devices like Cisco's DX600 shown here may be on the way out as workstyles change to reflect greater mobility in the office.

Over the years, there has been much talk about unified communications as ‘the next big thing’ for enterprise networks. So what’s the reality in Britain today? IAN GRANT finds out.

Unified communications (UC) dates back to the 1980s when the PBX started going digital and people began hooking it up to the firm’s IT systems, using it as dual-purpose voice and data router for local and wide area networking. Since then, voice has migrated to digital, effectively becoming ‘just another app’.

Today, UC is a set of applications that combine an organisation’s real-time and non real-time communication services. Real-time services include voice and video communications, IM, location, desktop and data sharing (including web-connected interactive whiteboards), call control and speech recognition. Non-real-time services include voicemail, email, SMS and fax. The growing use of social networking covers both sets. Usually, both types of service are delivered by optimised systems overlaid by a user interface that provides a consistent way of interacting with and between the services.

Switching packets instead of circuits has profoundly beneficial effects on network resource allocation and efficiency. With ISDN, voice over twisted copper pairs takes 64kbps per circuit; Bell Labs researchers have achieved speeds of 10Gbps in controlled environments but only over 70m. They have also got twisted pairs to deliver 1Gbps symmetrical broadband – a current world record, but again that was only in the lab. Real world copper networks struggle to deliver 2Mbps over more than 1.2km, hence the universal push for more fibre in the networks, ideally to the premises.

The change began in the early 1980s when digital networks started to implement statistically multiplexed packet switching (IP) rather than TDM (time-division multiplexing) switched circuits.

It accelerated when the internet took off, starting in the mid 1990s, and again a decade later when it became possible to deliver high quality VoIP. This was thanks largely to better codecs for handling digital streaming, Skype, which popularised the technology, and the development of SIP to emulate the plain old telephone system to set up and take down calls.

Now the network flags different types of content and applies different QoS policies to them when prioritising packets. At the receiving end, the ‘edge device’ sorts the packets into their appropriate streams and delivers them (hopefully in the right order) to the right end user device.

The ‘plumbing’ that enables UC to be a fast, clean, happy user experience is complicated. Incumbent telcos introduced outsourced PBX-type systems based on the telephone network. When the internet arrived, entrepreneurs found a way to emulate PBX services using VoIP and SIP, and to integrate email, IM and other services. These have proliferated into specialised server devices for voice, video, email, security, etc, which must all be supplied and managed, but at a much lower price point. Initially, the transmission cost was the price of a phone call. Later, as firms either set up their own in-house networks or subscribed to an internet service, it became largely free and was built into the price of a broadband or leased line subscription.

UC in the UK

Ofcom’s communication market report published in August says that although the total number of fixed lines in the UK is now 33.4 million, the percentage of VoIP users is now 35 per cent of the population (i.e. about 22.8 million).

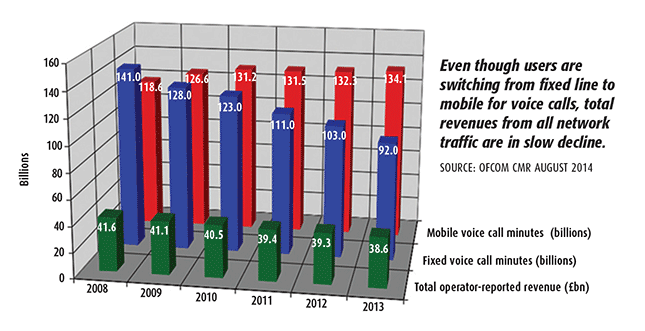

As VoIP users trebled between 2008 and 2013 the effect on fixed and mobile operators has become clear (see graph). The growth of mobile minutes slowed and fixed line minutes crashed from 141 billion to 92 billion, driving total operator-reported revenues down from £41.6bn to £38.6bn.

Market researcher Illume estimates that SIP trunking now represents around 30 per cent of the total connections and predicts there will be more SIP trunking than ISDN by mid-2016. “The hosted VoIP market in the UK reached 1.4 million at the end of June and there were 1.2 million SIP trunks,” says Illume director Matthew Townend. “Although the hosted market has been growing well, it is still probably around eight per cent of the installed base, and has been held up by a lack of available fibre. But with the fibre investments now being made, we expect this growth to accelerate.”

He goes on to say that traditional voice users are finally “engaging strongly” with hosted VoIP, adding that this was demonstrated by the recent launch of the Greensky hosted voice service by Nimans.

UC offers many advantages such as savings from lower travel costs and slashed mobile phone bills, having only a single network to worry about, and not dealing with itemised phone bills. But arguably, UC’s greatest appeal is the increased staff productivity that it leads to.

Ray McGroarty, Polycom’s director for enterprise UC Solutions, says: “When you have UC it makes it quick and simple for your employees to use the right communications method for the task.

A process that might have taken 50 emails over the course of a week can now be completed in real-time.”

He adds that the advent of cloud-based UC as a Service has helped quell cost concerns. “With UCaaS, the upfront investment has been drastically reduced and has largely eliminated the cost of refreshing equipment and the risk of obsolescence.”

IP transport equipment vendor Sonus believes cloud UC shifts costs from “CPE plus capex” to “cloud plus opex”. It also frees businesses from the complexities of providing full, ubiquitous, cross-platform BYOD and mobility for communications and collaboration. The company’s EMEA CTO Roger Jones says while cloud UC still represents a relatively small percentage of the market, it’s now beginning to take-off. “To give just a few examples that I’m seeing day-to-day: Worksmart is hosting Mitel UC; Outsourcery is putting in hosted Lync; and Broadsoft is doing it all over. We’re mostly seeing hosted Lync Enterprise voice and Broadsoft, but Mitel and Cisco are also out there, along with many others.”

Unified cons?

While there are some solid pros to UC there are also plenty of cons. According to Tony Bailey, Vodafone UK’s head of enterprise services, it should be regarded as an enabler for better ways of working and not the endgame. “UC cannot just be a technology project. The business needs to review how it is operating and consider people, processes and space to get the most effective use of UC. The cultural change can actually be the more difficult bit rather than the technology itself.”

As with any technology deployment, user uptake counts. “Managers need to offer education and support to make sure that their teams are using all of the communica-tions channels within the UC deployment,” advises Polycom’s McGroarty.

Paul Dunne, head of channel sales for UK and Ireland at Plantronics, agrees.

He warns firms not to underestimate the organisational changes that come with run-ning a UC system, or the amount of support users will require. “Businesses will get the best results by encouraging the improved collaboration offered by UC and by providing employees with the appropriate hardware to bring the technology to life.”

He adds there’s a lot of confusion about the best way to unify communications technologies. “There are two basic models [firms] can choose from: a network-centric model and a software-centric.

“In a network-centric model, the functionality of users’ dedicated endpoint devices depends on a tightly managed ‘smart’ network. Communications applications reside and depend on a single, secure network, and extensive QoS mechanisms must be in place for all links.

“In a software-centric UC model, devices run multifunction software on any network, independent of smart network functions – although they can of course relate to these if needed.”

McGroarty says managers should also set realistic expectations as the internet is a “best efforts” business – i.e., operators prom-ise to do their best to deliver the packets as quickly as possible but offer no guarantees. As a result, many UC deployments suffer from variable quality and reliability. Users may have problems setting up voice or video calls, and when they get through, they might experience poor AV performance and/or low quality interactivity.

“UC is only as good as the network on which it runs. Connectivity, bandwidth and routing efficiency will differ across your office locations, customers and partners. You need to treat all your solutions and services as a whole when deploying UC. Things to consider include your exchange services, LAN, WAN, call admission control, and any legacy systems such as PBX,” says McGroarty.

Vodafone’s Bailey agrees: “IP telephony did very little for the users (just a change of telephone set on the desk), whereas UC can transform the business network.”

Quality of service

Citing evidence from built-in quality of service monitors, the International Multimedia Telecommunications Consortium (IMTC) suggests that 60 to 80 per cent of UC QoS problems originate in the underlying network. Its members are trying to develop standards to ensure the interoperability of real-time, rich media communications. They include hardware makers such as Ericsson, Huawei, Nokia and ZTE, network operators like AT&T and Orange, as well as UC specialists Avaya, Plantronics and Polycom.

Troubleshooting the problems is no mean feat. Even when they are identified correctly, addressing them may require infrastructure upgrades or network reconfigurations, which means total cost of ownership can take a big hit. Dunne points out that VoIP depends heavily on the QoS configured correctly within an enterprise’s network because IPT uses a statistically multiplexed packet-based model to optimise bandwidth.

And Vodafone’s Bailey cautions users who expect UC to be as reliable as their telephony: “The management and monitoring is more about the performance of the application than the underlying network. Network managers need to make sure that they have the right performance applications in place so users can use UC to its full capacity.”

The IMTC is pushing to separate the different classes of services (CoS) using a differentiated services model. This allows an expedited forwarding per-hop behaviour to prioritise the delivery of real-time interactive media traffic such as VoIP over other CoS like email and SMS. This will also address security. “As VoIP technology got pervasively deployed, a security model evolved in which voice was separated from other network traffic using a VLAN model. This ‘lock down’ model puts voice and data traffic on separate VLANs and only traffic from the voice VLAN is marked for expe-dited forwarding,” states the consortium.

This model also meant that only purpose-built VoIP handsets could gain access to the voice VLAN; permission depended on a VoIP device credential owned by the voice administrator and user devices were shut out.

Network vendors pushed this model for different reasons, including the ability to mitigate malware and to prevent DoS attacks on the VoIP service, which they sold as mission-critical. But their approach became outdated as VoIP evolved to UC and collaboration (UC&C). The IMTC says: “Converged UC&C endpoints support many modalities using a single connection: voice, video, and data are now typically converged over a single network interface, which precludes the use of dedicated voice VLANs for securely applying QoS markings to VoIP traffic.

“Some UC&C endpoints attempt to address this issue by applying QoS markings to voice and video traffic as it enters the network from the endpoint device. However, most enterprise networks will not trust QoS markings applied by endpoints, and network policies usually re-mark untrusted traffic to Best Effort.”

The IMTC adds that other QoS techniques rely on deep packet inspection to classify traffic according to its content and apply QoS markings based on this classification. However, it says these techniques are increasingly unreliable because of a growing trend to encrypt by default all calls and signalling traffic end-to-end. The organisation hopes to address these issues by using dynamic flow parameters such as IP address and port information. It has set up a programme to investigate the use of software defined networking (SDN) to implement them.

“By allowing UC infrastructure to interact dynamically with the network, we aim to ensure that application level quality and performance requirements can be met by the underlying network infrastructure,” said the IMTC in a statement announcing the move earlier this year.

This would work using an automated QoS network service application in the UC&C infrastructure that specifies the flow parameters dynamically to the network at call setup. An SDN controller would then pre-warn the rest of the network to trust these QoS markings. As a result, traffic flows would become simplified and speedier because the network wouldn’t need to read every packet – only the QoS marking and address.

What’s hot in the market?

Recently, many companies have acknowledged that social network media are replacing UC features such as IM. Some of the bright young things that made this possible, like Yammer and Jabber, were bought by bigger players (Microsoft and Cisco respectively. Microsoft of course went on to develop Lync, its own UC suite, as well as purchase Skype.

Initially, large firms with their own private networks were the main UC users, running platforms from their own data centres to branch offices. Since then, third-party data centres have arisen to provide UC as a service over broadband, in hosted as well as managed formats, mainly to SMEs via cloud. Both they and in-house UC operators now face challenges from web-scale cloud operators who offer UC ele-ments as part of their services, such Google with Hangouts or Microsoft with Azure.

There are also open source products, and one of the more widely-known is Asterisk. Users and developers can effectively build their own UC systems, or they can buy a fully-fledged platform from Elastix which uses Asterisk as its base. Originally designed for Linux, Asterisk runs on a variety of operating systems including NetBSD, OpenBSD, FreeBSD, Mac

OS X, and Solaris. It is small enough to run in an embedded environment using customer premises equipment with OpenWrt, or even on a Raspberry Pi.

Avaya and HP Enterprise Services have announced a multi-year agreement to offer cloud-based UC and contact centre tech-nology, as well as new UC management solutions for enterprises. The deal seeks to combine HP’s cloud services delivery with Avaya’s UC and contact centre portfolio to create a one-stop shop for mobility applications, software, and networking for UC and customer experience management in an XaaS wrapper.

Vodafone has developed a portfolio of UC products under the One Net brand. These include One Net Express and One Net Business for micro businesses and SMEs, through to One Net Enterprise and One Net Global Enterprise for larger organisations.

One Net Enterprise is already available in six European countries but was formally launched in the UK as we went to press in early September. The platform is pitched at public sector and NHS clients, and features a voice/video/IM/presence suite which also hooks into Microsoft’s Lync and 365 apps.

Phil Mottram, the new head of Vodafone UK’s enterprise business, argues that once UC is widely implemented it can help public sector bodies meet austerity budgets that address the £22bn annual deficit.

He declined to name the half dozen large UK firms piloting Net One Enterprise but added: “We’re also pitching it at the M2M sector, and we find the ‘wearables market’ in healthcare extremely interesting.”

Meanwhile, after years of working with Vodafone, just weeks ago BT leveraged its new mobile virtual network agreement with EE to launch One Phone. This will essentially compete with One Net and to provide in-building LTE-based office communications services in competition to Wi-Fi-based vendors.

-(002).png?lu=245)