30 June 2014

London’s once futuristic looking cityscape is still largely bereft of fibre connectivity.

We last covered the government’s SuperConnected Cities programme in September under the headline: “City networks? We’ll get back to you”. Well, a couple of folks have now returned the call. IAN GRANT lends an ear.

Britain is spending almost £5bn a year to accelerate ‘next-generation access’ (NGA) to high speed networks. But so far, politicians and regulators have largely ignored the needs of enterprise. That changed slightly with the launch of the government’s £150m SuperConnected Cities (SCC) programme in March 2013.

After a controversial start that saw BT and Virgin Media object to cities buying fixed lines on behalf of local businesses, things settled down. The Department of Culture Media and Sport (DCMS) picked 22 cities for a voucher programme. Under the scheme, firms may apply to their city council for a grant of up to £3,000 to defray the cost of connecting to a high speed network service that provides a “step change” in the speeds they enjoy. Running costs are for the businesses’ accounts.

That figure of £3,000 needs to be seen in context. Broadband Delivery UK (BDUK), the DCMS agency charged with delivering high speed broadband across the country, has mooted an urban benchmark price of £150 connection plus £50 per month for a 30Mbps (copper) line. Independent telecoms consultant Mike Kiely says this needs to be seen in the light of the emerging average European wholesale line price of €15 to €20 for a fibre connection capable of 1Gbps and €50 for the connection.

Analysys Mason principal analyst Rupert Wood notes fibre connections are much more freely available in Europe than the UK. His figures suggest connection fees of under €50, and monthly costs of around €30 for a >30Mbps consumer-grade line, or just over €100 for a business-quality service. He adds that these products are all aimed at the low-end Ethernet market and may not include backhaul costs.

Copper to rule fixed last mile access

Sources ranging from the National Audit Office to former BT CTO Peter Cochrane have questioned whether the billions spent on the UK’s physical infrastructure for communications will produce a network that’s fit for purpose in an age of global competitiveness.

Like most incumbent telcos worldwide, BT has opted for copper-based VDSL2 technology. This means running fibre from one of 15,000-odd exchanges or aggregation points to street cabinets, and completing the link to the customer with copper local loops. Later, the company is expected to extend the fibre to street distribution points and to upgrade its VDSL technology with vectoring (a noise cancellation technology) to increase speeds over the final copper drop to 1Gbps.

Meanwhile another new technology, G.fast, is an extension of VDSL that proposes to give 1Gbps over short (<250m) copper loops. But Openreach spokesperson Gemma Thomas says BT is “unlikely” to introduce this any time soon because the ITU has not yet finalised the specification. Thomas says that while tests using early prototype kit have gone well, BT will wait for the formal standard and for equipment makers to reduce it to silicon before adopting it at scale.

She estimates that this will take three years, and also points out that BT will not try to gain first mover advantage and go it alone because its network “had to be used by other network operators”.

While Virgin Media has installed a lot of fibre for backhaul, its last mile still uses copper coax cable. With DOCSIS 3.0, this combination can provide customers with >150Mbps downloads. And while mobile operators promote LTE-based high speed mobile broadband, the fact is that it will remain rare, costly and contended, and therefore unsuitable for many businesses. Furthermore, it will increasingly need fibre for backhaul.

Britain has lots of fibre – but not much of it is available to retail broadband customers or even to wholesale broadband customers on agreeable terms. So for the moment, optical cables remain too rare and costly. But they are inching closer to widespread commercial viability as competition emerges downtown.

Has the voucher scheme worked?

The cities in the SCC programme include: Aberdeen; Belfast; Birmingham; Bradford; Brighton and Hove; Bristol; Cambridge; Cardiff; Coventry; Derby; Derry City; Edinburgh; Leeds; London; Manchester; Newcastle; Newport; Oxford; Perth; Portsmouth; Salford; and York. So far, 422 suppliers have registered to service the scheme. DCMS says some 149 have provided quotes, and 90 have won business.

By the end of May, these cities had issued 1,008 vouchers. The fixed/wireless connectivity split was 77/23 per cent, and the average speed per connection went from 11.2Mbps to 70.3Mbps for downloads. DCMS says it will provide a city-by-city breakdown later this summer, but refused to say how much money has been paid out so far (Networking+ estimates the figure to be around £3m) or to whom it has gone. However, Virgin Media tops a DCMS table of suppliers that have been issued vouchers.

BT – which Ofcom says has an effective monopoly on wholesale fixed line access despite Virgin Media’s efforts – declined to say how many vouchers it has won. Nonetheless, its Openreach division is likely to be a big winner. This is because smaller operators like Hyperoptic and TalkTalk rent ducts and lines from Openreach, even as BT’s Business division competes with them at a retail level.

So does 1,008 vouchers issued in 14 months represent success or failure? To be fair it’s probably too soon to tell. But there’s not much time left – DCMS says the money dries up in March 2015.

The network operators remain optimistic. For instance, Mike Smith, business director of SME propositions at Virgin Media Business (VMB), says: “The future of the scheme is looking good and is continuing to gain momentum, with the number of applications on the rise.”

Kate Rennicks, who is responsible for running the voucher scheme at fixed/wireless operator Metronet UK, says her firm has connected 200 firms so far, and has a backlog of 1,000.

For Hyperoptic, getting into the scheme meant starting its business division almost from scratch. Its standard offer addresses residential consumers who live in “multi-tenant dwelling units”, i.e. blocks of 60 flats or more. To date, it has connected more than 150 buildings in London, Reading, Cardiff, Bristol, Manchester and Liverpool, and is looking at other SCC cities. Commercial director Darren Shenkin won’t disclose how many subscribers Hyperoptic has but adds that its fibre passes more than 35,000 homes. Now the company wants to extend that connectivity to business users. “We’re taking the business market very, very seriously,” says Shenkin. “We’ve only just built and are still adding to our business sales team. There’s been a lot of money and focus on bringing consumers into the 21st century, and we want to do that for SoHo firms and SMEs.

“He goes on to say that Hyperoptic is collaborating with the 22 SCC city councils to boost demand: “We’re working with them to pull marketing collateral together to go after SMEs in those cities.” Hyperoptic’s first approach was to 7,000 businesses in London’s Covent Garden in mid-June, and it is also talking to some SCCs in which it does not yet have a residential presence.

Rennicks believes that a lot of service providers registered as SCC suppliers on a “just in case” basis without seeing the voucher scheme as a big opportunity. Metronet UK grabbed it with both hands. If the company’s claims are accurate, it has taken a fifth of all the vouchers issued so far and most, if not all, the wireless business.

But she points out that it wasn’t easy: “This scheme required us to change the way we deliver service. Effectively, we had to re-engineer our back-end processes. You’ve got a different type of sales cycle where you have to get a customer to fill in an application form, then help them with the paperwork afterwards. I guess not all suppliers are necessarily willing to do that. With a turnover of around £12m, we’re a fairly nimble company. Compare us with BT, which has very entrenched processes, and we’re able to do that quite quickly.”

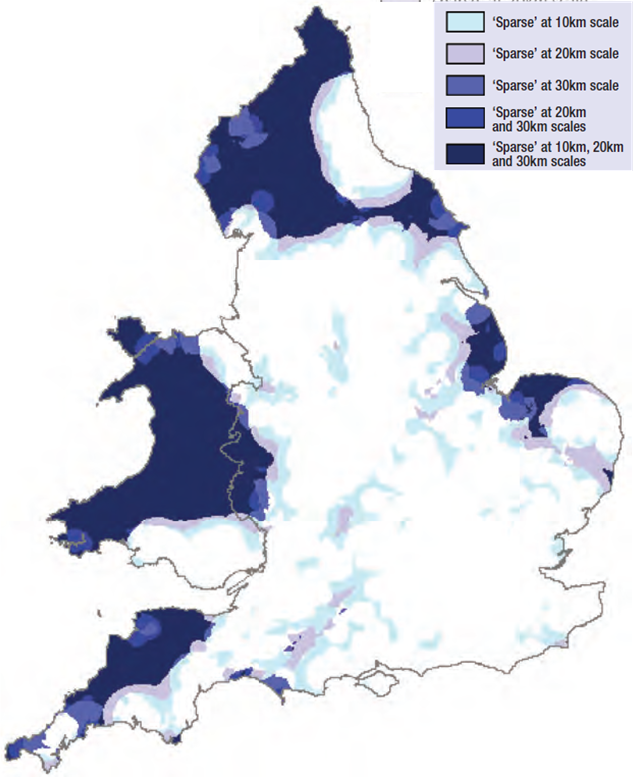

Population ‘sparseness’ is a measure of the number of addresses per hectare at different scales. The bluer the area, the fewer post office addresses there are at all scales. SOURCE: PETER BIBBY, DEPARTMENT OF TOWN AND REGIONAL PLANNING, UNIVERSITY OF SHEFFIELD

The ‘Final Five per cent’

A fifth of the UK’s population lives outside of towns and cities, and almost all are desperate for better broadband connectivity. To close the ‘digital divide’, the government is spending 10 times more on rural broadband compared to its SuperConnected Cities programme. The investment is being made almost exclusively through BT, but there is growing suspicion that the firm might not deliver what residents expect from the £1.2bn Broadband Delivery UK scheme.

Earlier in June, the government announced plans to spend up to £10m on a set of “innovative” pilot projects that, if scaled up, might ensure the ‘Final Five per cent’ gets the same broadband speeds at the same price as urban users (for a list of the projects see networkingplus.co.uk).

David Cameron has acknowledged that access to high speed broadband is no longer a luxury but a “necessity” for rural areas. Starting a small business is how people survive in such areas. According to the Office of National Statistics, in January this year there were 486,000 rural businesses employing 3.1 million people. It says the number of registered business per 10,000 people was 655 (in urban areas the figure was less than half that). But they were almost all tiny – 93 per cent in a “sparse rural setting” had fewer than 10 workers.

On average, sparsely populated urban businesses’ gross turnover is £93,000 more than their country cousins, but productivity in rural areas is higher: Average turnover in sparse villages was £76,000 per employee; in sparse towns it was £63,000. Even so, total sales of rural businesses were less than 10 per cent of that of urban businesses.

Therein lies the network builders’ quandary. The demand for high speed communications is unquestionable, as is the impact it could have on rural productivity and economic growth. But rural communities are more expensive to reach and don’t guarantee a ROI for operators.

But arguably, that’s only if you stick rigidly to free market economics. It’s never worked that way among farmers. Grouchy they may be, but they do mostly live up to their sense of community. That sense has enabled farmers in Lancashire to build a 1Gbps fibre to the home network called B4RN, or Broadband for the Rural North. Built without a penny of government money, and in the face of official and BT opposition, the community-owned not for profit operator is steadily lighting fibre to more farms and villages, and is also attracting neighbouring communities who can’t wait for BT to deliver.

B4RN has also encouraged emulators around the country, and the innovative thinkers benefiting from the new government money. But it takes brave people to invest knowing that they might end up competing with BT, especially when they find the official dice, by fortune or design, still loaded against them.

Flexible pricing for fixed lines?

For Hyperoptic, the voucher scheme has helped to overcome another barrier: the cost of connection to a leased line. Openreach’s prices for General Ethernet Access (GEA) – which is what Hyperoptic resells extensively – are £92 for connection, £436 per year rental for 100/30Mbps down/up links, plus £2,000 for GEA Cablelink which connects the service provider’s backhaul and servers to the BT NGA network.

Controversially, in May BT increased prices for its wholesale Fibre On Demand (FOD) product which provides 330/30Mbps, blaming unexpected costs. The FOD connection fee is now £750, line rental is £1,188 per year, and there is also a “distance charge” to cover the link between premises and the nearest aggregation point that ranges from £350 up to 200m to £6,125 for 2km. Prices for longer runs are on application, but BT says 96 per cent of premises are within 2km of an aggregation point.

Some critics accuse BT of raising the price to eat up the money from the SCC voucher scheme. But Analysys Mason’s Wood reckons it’s more likely due to the telco trying different things to see where the demand lies. He says possible large traffic clients include business parks and new residential developments.

BT’s dominance of the fixed infrastructure provides both a base and a pricing umbrella for other network operators. VMB’s Smith says: “The UK market is one of the most competitive in the world offering great value; as such [SCC has had] minimal impact on the price for internet connectivity. Within the bounds of the scheme, bespoke tariffs are being created by suppliers to allow SMEs to really make the most of the voucher scheme.

“Shenkin adds that Hyperoptic has been able to connect some voucher customers for as little as £300. “We’re not looking to take advantage of the scheme. So we pass back to the business costs that are true and accurate, and reflect the costs we would incur for bringing that connection to them.”

The SCC voucher scheme is allowing Hyperoptic and others to think in wider terms. Shenkin says the firm is targeting business parks as well as smaller, mixed use dwelling/business units. For instance, Hyperoptic now offers a company located in a business park or a mixed use building a 100Mbps service for £350 per month. If customers are prepared to share their bandwidth with others on the site, their monthly rental comes down substantially. But Shenkin points out that the decrease is not proportional to the number of sharers because Hyperoptic incurs extra management costs.

CityFibre is also thinking laterally. The dark fibre network builder has just added Coventry to its footprint of Bournemouth, York and Peterborough. Commercial director Mark Collins says a joint venture with ISPs TalkTalk and Sky in York and other cities aims to explore the viability of alternatives to Openreach for fibre infrastructure for homes and businesses. TalkTalk also has a carrier deal with fastgrowing US-based wholesale network operator Zayo (News, p2) which recently bought dark fibre specialist Geo Networks (News, May 2014). Through Zayo, TalkTalk will have access to FibreLink, the Welsh government’s £30m network that serves business parks in North Wales, and which is threatened by BT’s part taxpayerfunded Superfast Cymru rollout. The issue is presently the subject of a complaint to the European competition authorities.

CityFibre has just raised £30m on top of its initial £16.5m from its January IPO to fund its Gigabit Cities programme. Collins says the firm is now “fully-funded” to build fibre backbones in more than 20 cities, and pass more than one million homes, business and public sector sites by 2016.

Key to CityFibre’s plans is to first get city councils on board and then large users such as ISPs and mobile network operators. It should be easy: the mobile operators are keen to roll out small cell technology (which use LTE and Wi-Fi) to offload and backhaul mobile phone traffic. Vodafone has already complained about the cost of renting BT’s lines and the growing shortage of microwave spectrum. It bought Cable&Wireless for £1bn to acquire its own fibre capacity and avoid a squeeze from BT.

Collins says these candidate customers don’t see BT’s FTTC network delivering what they or their customers want. “VULA (virtual unbundled local access) effectively re-monopolises [local] access. Customers don’t have as much control as they do over local loop unbundling. With GEA or VULA they are much more under the control of BT. There is also a concern that they can be price-squeezed – TalkTalk has been vocal about that.”

In fact, Ofcom has now dismissed a TalkTalk complaint against BT, but agreed to consult on BT’s margin pricing activities to ensure it does not abuse its monopoly in local access.

Another operator exploiting wireless for metro networking is UK Broadband. Ofcom is presently consulting on giving the PCCW subsidiary a permanent licence for its 124MHz holding of 3.4GHz spectrum, on which it has built its new TD-LTE-based high speed connectivity product, Relish.

UKB chief executive Nicholas James says the request for an extension of its licence is a normal part of his long-term planning. “Our 4G licence is now the only one that has not been extended indefinitely by Ofcom. We are pleased the regulator has now recommended bringing UK Broadband’s licence into line with the rest of the market and recognised that doing so will promote competition and encourage investment and innovation in the UK.”

UKB has registered as an SSC supplier, so for now central London SMEs can get vouchers for a dedicated wireless connection at speeds ranging from 20Mbps to 1Gbps with a 4:1 down:up speed ratio. Mobile users can access the network via a pocket hub. UKB promises next day delivery to home and SME users, and a dedicated link within 10 days.

James claims that Relish offers a real alternative for customers that have suffered slow speeds, setup delays and are forced to buy landlines they do not want. He is referring to research UKB commissioned prior to launching Relish that revealed London SMEs resent having to rent a voice service in order to access broadband, and that most residents and SMEs could live without one. James reckons this “landline tax” costs residents and SMEs £156m and £37m a year respectively, adding landline charges had risen almost 70 per cent in 10 years – far quicker than inflation.

The need for speed

Collins, Rennicks and Shenkin note the need to cultivate demand. All agree that DCMS has proved more flexible than one might have thought. Originally, the SCC scheme required two quotations from ISPs. This was a barrier for SMEs. Following talks, the government relented, breaking the logjam. VMB’s Smith says: “It’s encouraging to see the pragmatic response from DCMS who have constantly listened to the market and responded through the early stages of the scheme. There have been some important changes since the scheme launched, all geared to making the process smoother for those businesses applying.”

Smith claims VMB has been at the forefront of the scheme, working with all participating cities to help SMEs benefit from the money on offer. But what’s in it for such firms? True, they get £3,000 towards connection costs, but usage costs can dwarf that. Smith says the connection contribution can make a “tangible difference” to how a company operates. “Many local businesses have already reported stronger growth and smoother day-to-day operations following a successful application.”

One such firm is Croydon-based DMC Business Machines which sells printers, copiers, scanners and consumables nationwide. It was one of the first applicants and used its voucher to upgrade from a 10Mbps ADSL broadband line to a 30Mbps symmetrical connection from VMB. DMC IT manager Kevin Streatfield says the firm had maxed out its 10-meg line: “On average we’re using 25-30 per cent of the new pipe throughout the day, but it’s early days. I sleep better at night knowing we are not bumping up against a capacity ceiling.

“What’s more, we are at the cutting edge of the Internet of Things. The business machines we install on client premises increasingly tell us about whether they need a service, have a fault or simply need some new toner. The DMC mothership needed more bandwidth to cope with the smarter business machines on client premises.”

Streatfield adds that for his firm, it’s all about the uploads: “The marketing guys might view videos online and upload ours to YouTube, but mostly it’s about our engineers, sales people and customer service reps uploading data to our enterprise systems. Having a symmetrical connection makes all the difference rather than an old ADSL one.”

-(002).png?lu=245)