21 April 2016

Gone are the days when metropolitan area networks required the clout of the big telecoms companies or city councils to build costly physical infrastructure such as fibre cabling.

In the 1990s and 2000s, the metropolitan area network (MAN) model was one that organisations with a requirement to link multiple office sites around large built-up areas viewed with favour. The rampant technological proliferation of the time decreed that no LAN remain an island, while the joys of corporate connectivity had won over many a board’s approval for greater networked IT investment.

Options for connecting enterprise computing resources beyond the local area were, however, still prescriptive and pricey, and had to be bought from telecoms companies. For city councils especially, who might wield clout enough to build-out their own physical infrastructures by laying fibre through existing municipally-owned ducting routes, MANs promised ongoing operational expenditure efficiencies, extended ownership of ICT estates, and a basic blueprint for future network development.

In the pre-high-speed broadband era, the opex gain alone was sufficiently compelling for all the private and public sector organisations whose LANs otherwise had to be linked via expensive, enterprise-strength leased lines or ISDN circuits; the desire to get away from the telco’s (i.e. BT’s) clutches was a prime motivating factor behind many MAN implementations.

A ‘datacoms rings main’?

Then as now, definitions of what a MAN is (and is not) varied, and in these days of doctrinaire technological convergence, the kind of network design that the acronym might now be applied to probably obfuscates as much as it illuminates.

Back in the day, for instance, MANs were sometimes described as datacommunications ‘ring-mains’, i.e., being of looped, circular configuration. But this is not necessarily a defining characteristic.

Neither, for that matter, is the use of ‘metropolitan area’, notes Matt Yardley, partner at Analysys Mason: “MANs have never really been city-wide. They were generally built in very specific geographic areas targeting certain customer segments – for example, COLT focusing on financial institutions in the City of London.

“Newer network operators, like CityFibre, are now constructing MANs connecting public sector buildings as well as targeting businesses. [So for] business connectivity, MANs can still be important as they can lower the cost of service provision.”

Arguably, although several old-school metro networks are almost certainly still chugging away around the country, the heyday of the telco-busting MAN was relatively short-lived. By the late 2000s, maintaining and managing even these sizeable network infrastructures (which could, of course, extend over miles) became rather onerous for network managers, especially as the telecoms industry unbundling and other pro-competitive regulation resulted in the availability of more affordable broadband connectivity options that could service their core applications’ basic communications needs.

The issue for MAN owners appeared to turn full circle: in many TCO cases it was more cost-effective to outsource inter-office datacommunications to service providers. More recently, wireless communications media – such as mobile data and Wi-Fi – have undermined the case for embedded and enclosed city-scale network infrastructures of the older variety.

According to Falk Bleyl, product director at Updata, the world simply changed around first-generation MANs, leaving them often under-utilised or even unused. “MANs have typically been deployed to provide high-capacity connectivity between an organisation’s sites within a relatively confined geographic area,” he says. “Organisations benefited from the higher bandwidths, but then faced challenges due to changing organisational needs, network estate changes and rationalisation, as well as continued budget pressures.”

Bleyl adds that long-term MAN ownership means that organisations could also face challenges in terms of security and segmentation of VPNs, as well as attracting and retaining the engineering skills needed to operate the network – especially if the asset is based on technology that’s now showing its age and is not cost-effectively upgradable.

By the start of the 2010s, MAN appeal had started to fade. And where they were kept running, their fibre capacities were utilised to fairly minimal degrees.

So the term ‘metropolitan area network’ is not one that Chris Wade, commercial director at TNP (The Networking People), says he and his colleagues hear too much these days: “Where it is used is in the context of what would now be more closely defined as a ‘community of interest network’. And in this context it should aspire to deliver pervasive high-speed connectivity to a city’s municipal infrastructure, plus support digital outreach in areas of poor connectivity or usage.”

Standard virtual networking solutions supporting business applications have also rendered the physical MAN’s attractions less compelling. As Yardley says, although MANs now tend to be thought of as being built and operated by newer entrants to the market, it is important to note that established players, such as BT and Virgin Media, also serve the business market. But here, he points that the architecture of their networks does not follow the ‘typical’ MAN setup, mainly because their networks are much more extensive geographically.

If you build it...

The service propositions from new market entrants referred to by Yardley have renewed interest in the MAN concept over the last three years. These arriviste network operators – and names such as Commsworld, Hyperoptic and the aforementioned CityFibre and TNP spring to mind here – have been re-energising the MAN idea.

Although these ‘metro area nets’ represent a different commercial proposition to their antecedents, their general principle remains the same.

Among their objectives is the introduction of a new competitive front in the high-speed, high-capacity broadband stakes. Their operators can also be motivated by an interest in accelerating the speed of digital change mandated by government for the UK’s regional metropolitan centres.

In addition, some of these new networks offer multi-play service offerings for businesses and home customers on top of basic connectivity, sometimes featuring voice and video into the bundle mix. They compete against each other and against bigger incumbents like BT Openreach (which has responded with copper boosting techniques such as G-FAST) and Virgin Media (which is exploring opportunities afforded by hybrid coaxial/fibre networks). But the driving differentiator is their aim to deliver up-to gigabit speed broadband services to cities where, hitherto, business customers needing those top speeds would have been left wanting.

Gigabit connection speeds might at first sight seem over-egged for general business applications. But there are also many vertical sector applications where such capacity is standard for a range of applications and workloads. These may be for companies in small, specialised scientific and media fields which are locating away from the high rent/high business tax south-east, and are focused on taking advantage of financial incentives to base their operations further north. With gigabit speed broadband access options they have everything they need and can get in and around London.

The new fibre networks have moved fast to establish their own all-fibre infrastructures, partly by build-outs and partly by acquisition of existing fibre optic network assets, such as CityFibre’s £90m acquisition of KCOM’s national fibre and duct network assets at the end of 2015.

The arrivistes’ ambitions are founded on the notion of ‘if you build it, they will come’, a belief shared by the plentiful venture funding that’s underwritten their strategies. Investors are betting on the viability of these new players ability to attract new customers, pull existing subscribers away from the incumbents, and then perhaps go on to become significant forces in challenging the incumbents in higher-value regions of the market.

In the space of two or three years, some have established estimable market presence and customer names. A signature factor here has been their support for, and championing of, the ‘Gigabit City’ concept. The term ‘Gigabit City’ has been talked-up by technology providers and municipal agencies as something akin to a hallmark of civic achievement, although whether gigabit MANs will deliver on their promise, and repay their investment, has yet to be ascertained.

Gigabit cities

Strategies vary, but a unifying objective is the creation of a string of UK gigabit cities – places where symmetrical access speeds of 1,000Mbps are available. Cities so far named as possessing Gigabit status include: Aberdeen, Bristol, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Coventry, Liverpool, Nottingham, Peterborough, Reading, Sheffield and York.

Coventry’s Gigabit ambitions are of particular interest in the old MAN/new MAN context, because they are founded on 142km all-fibre network commissioned by its City Council to serve its public sector estate back in 2008. By 2010, it had connected some 306 buildings, including public sites such as municipal offices, libraries and community centres, and replaced leased lines and data circuits to all main council buildings and local schools in the wider Coventry area.

The Coventry Council MAN infrastructure was sold to CityFibre in June 2014, and the network will still be available for the council to continue to use until 2029. The council says that it was always a secondary ambition of the project to commercialise any spare capacity, although in real terms, the sale commercialises nearly all capacity. In the intervening years Coventry City Council attempted to resell spare MAN capacity, but with limited success. It has only been with the arrival of opportunistic small network companies such as CityFibre, who were interested in buying its MAN outright as a way of ensuring that the asset was developed, that its full potential to benefit the city’s commercial needs have been fulfilled.

So does the Coventry experience suggest that other semi-lit or dark MANs could be dusted down, sold off and switched on again under new commercial ownership? Probably not, says Jon Lewis, director of strategy at Telensa: “It is often difficult to resurrect old networks. The expertise needed to manage them is hard to find, and replacement parts may simply not still be available.”

Besides, as Lewis suggests, the cost of new networks is “an order of magnitude cheaper” than reviving old infrastructure. However, Analysys Mason’s Yardley thinks that it’s possible that there are public authorities around the UK who own telecoms infrastructure for internal network purposes – CCTV, for example – and may consider offering those assets to the market.”

The necessity for any new MANs to have opportunities for monetisation built into their raison d’être will be another signifier of change for the MANs of the future, according to Alastair Williamson, head of global sales at Ranplan. He believes the potential for monetisation via supported services or applications absolutely must be factored into new-build or revitalised metropolitan area networks.

“As an example, the planning of networks has traditionally been coverage-driven. In the data-limited paradigm we now live in, planning networks needs to take into consideration the different types of revenue-generating services that customers will be using to ensure that the capacity delivered through the network will meet the end-user requirements.”

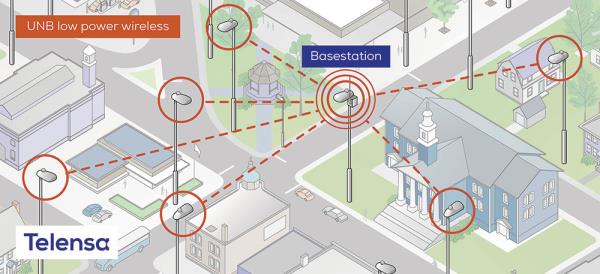

Telensa agrees. Any revitalised or new metro-scaled network certainly needs to be “built on a commercial foundation”, says Lewis. Telensa provides wireless remote control of street lighting. As Lewis explains, it connects the lights and associated sensors (parking, motion, weather) wirelessly across cities or wider regions, using its own ultra-narrow-band technology, running in unlicensed ISM (industrial, scientific, medical) bands.

He says: “Telensa’s wireless network uses tiny amounts of data; it utilises the city’s own infrastructure and it is owned by the city. So this is a very low-cost network. But it has to be because the solution has to be paid for by street light energy and operational savings.”

Lewis says the reason for this detail is to make it clear that MANs are deployed where a business case can be made to support their deployment and operational costs. “And because business cases vary, so different network technologies with different costs and capabilities will inevitably co-exist.”

Telensa says its wireless network utilises a city’s own infrastructure.

Smart City MANs

This same potential exists for MANs, wired and wireless, to facilitate Internet of Things (IoT) applications as they come forward, and especially IoT data backhaul and front-end processing.

“High-capacity, low-cost internet connectivity allows organisations and communities to do things differently, fostering collaboration and information sharing,” says Updata’s Bleyl. “Defined as ‘high-capacity connectivity between a single organisation’s sites within a relatively small geographic area’, for instance, MANs can be seen as a prototype of the Smart City ideal, extending the single organisation benefits to a wider geographic area, and to many organisations and even individuals.”

TNP’s Chris Wade agrees: “The true nature of Smart Cities is that the underlying networks must be pervasive, and most carriers who use the ‘build it and they will come’ model are not able to do this. They are limited by commercial models that insist on strict return-on-investment.

“Our experience is that true MANs, built on an independent basis should be the prototype for the Smart City as they will reach locations that commercial models do not hit.”

Meanwhile, Lewis reckons new models are emerging in which cities can control their infrastructures over the full duration of its lifetime. “Telensa provides wireless networks to cities which they then own. This means that the city avoids the potential for stranded assets, and can monetise the networks as it sees fit.”

The investment case for a MAN would also be improved if certain customer types – mobile operators, for example – were willing to sign long-term backhaul contracts. Analysys Mason’s Yardley says there is some limited evidence of this happening: “CityFibre clearly believes that there is a case to build new MANs, and their acquisition of KCOM’s assets is an indication that they are stepping-up their game.”

A final point worth highlighting is the importance of the regulatory environment in the entire context of MANs which should not be overlooked. For instance, Yardley says Ofcom is considering forcing BT to provide access to its passive assets (e.g. ducts) on a much more extensive basis than is currently the case.

While he suspects this could stimulate new investment in MAN-like networks, he reckons it would most likely result in ‘cherry picking’ – i.e., operators targeting the most lucrative areas – rather than any large-scale, city-wide deployments.

-(002).png?lu=245)